Tension, forces, confinement and liberation are transcendental categories. In his signature works, Robert Motherwell paints ovals and thick bars that seem to express just these transcendentals, although they officially are Elegies to the Spanish Republic (the ovals are meant to be testicles of a bull, likely in a fight). They are breakthrough paintings, at any rate. An artist has managed to break through the wall and construct his own territory, or energy field. Another one of Motherwell´s series are the Opens: largely monochromous paintings with rectangular interferences that truly open stuff up and dynamise things (they would become more complex over the course of the years). Another transcendental category, very basic, probably that of encounter. Although Robert Motherwell had initially studied philosophy and likely was the most philosophically educated among the Abstract Expressionists, the metaphysics expressed in his paintings seems to come more tacit than in those of many of his peers. They are, probably, metaphysically less strong, bold and important than the paintings of Pollock, Rothko or Newman. But Motherwell was, above all, a supreme abstract painter, i.e. an artist. His intellectual purity expresses itself in the purity of his painting. He is a dweller on the threshold were art remains art and art becomes metaphysics. Or, he dwells in both of them territories.

Monthly Archives: October 2023

Mark Rothko and Purity of Vision

The truth-seeker strives to get to know ultimate reality, the most fundamental reality. If this quest is philosophical and metaphysical, it will also involve introspection. Therein, the truth-seeker will also encounter the truth of his own mind, as an integral element of that reality. Such a quest for truth will lead to purification. If you are lucky, you will finally encounter a purified vision of fundamental reality and a purified vision of the mind. Mark Rothko aimed at expressing “universal truths”. In the world of his time, there were no universal truths anymore. Actually, only in medieval, in ancient, in atavistic times there have been lifeworlds and experience realms that were wholly integrated in themselves, unitarian and universal (or so we are inclined to think). Ours is a time of partial truths and accumulations of expert knowledges. Since man cannot bear living in an environment of partial truths, Rothko sought for expressing universal truths, yet at the basis of a contemporary, appropriate worldview and knowledge about the world. (And, I reiterate, what is likeable about the Abstract Expressionists, respectively about modern artists, is that, in apparent contrast to contemporary artists, they wanted such things.) For Rothko, the artist has the task to create a “plastic equivalent to the highest truth” and not to reproduce the specific details of a certain object. Since he was also seeking for truth in art, i.e. the medium in which truth can be expressed in specific ways, he was seeking for an absolute power of painting in itself, revealed not in reference to something, but in reference to itself. Rothko struggled a lot. Like the other major Abstract Expressionists it took him many years, decades to come up with the ultimate results that then became his signature paintings. (Because of this, the art of the Abstract Expressionists, and of the moderns in general, has the charisma of being born out of a transcendent effort, of having been through something, whereas contemporary art has not and therefore deems intellectually powerless.) If you want to get to know reality and the reality of your mind in a fundamental way, you have to be very active and contemplative. It will require great effort. You have to progressively deconstruct traditions, inherited knowledge, ideologies, affiliations, etc. You will finally encounter a vision in which there will be not very much to see. It will be some rather undifferentiated primal ground. Yet out of the primal ground emerges everything; virtually, the primal ground contains everything. In terms of the reality of your mind, you will encounter the primal ground of the power of imagination, the basic capacity of imagination. If you have managed to encounter this in such a fundamental way, you will finally be in control of reality and of the power of imagination. You will have achieved versatility. You will be enlightened. The signature paintings of Rothko are expressions of fundamental reality and epiphanies of the purification of mind.

The primal ground is something primitive and tranquil, but also, and foremost, something extremely sophisticated and very active, agitated. The individual visions of the primal ground are somehow similar to each other, but they are also different and differentiated from each other. Also Ad Reinhardt and Barnett Newman came up with visions of the primal ground (respectively practically all the Abstract Expressionists sought to come up with such a kind of thing, with something primordial). I personally prefer Newman over Rothko. Newman´s signature paintings contain the “Zip”, a narrow vertical flash that emerges over an undifferentiated ground. Such truly is the basic structure of the world: a motif emerges out of, or within, a background. With the right mindset, you understand them both. (“Enlightenment” means: you can permanently switch between motif and background, you oscillate between motif and background: this is then the desired vision of (an internally highly differentiated) “unity” of all things.) Rothko´s paintings are more unclear. They are less internally differentiated. It is said that Rothko wanted to express the Sublime, the Divine, or that he wanted to express harmony. He wanted to create pacifying environments. He wanted to do something purely meditative. In contrast to this, Newman´s paintings are actually unsettling, even terrifying. They express the IN THE BEGINNING was the word, the Let there be light. They express basic creation, they express the event, something that rips, something that tears apart. Newman´s paintings express the Logos. With the “Zip”, the possibility of narration, of rationality, and therefore of eternal agitation, uneasiness, turmoil and tumult enters. Rothko´s paintings are pre-narrative. They are more oceanic or, if you may, they are more mud-like. Rothko´s paintings are more formulaic, they are more boring, they are weaker. They are, in their repetitiveness, even a bit silly and a bit stupid. But Rothko´s paintings are considerably more popular than Newman´s. Rothko is some kind of household name; Newman is not. If you are into sarcasm you may think this is so because Rothko is “less intellectual” than Newman. People do not want to be confronted with the Logos, especially not if it comes as an aggressive flash. They want to be lulled. Yet, first and foremost, Rothko, maybe more than Newman, actually has managed to create something truly iconic. Rothko´s paintings are more like – paintings (Newman´s actually are more conceptual). Maybe more than Newman´s, Rothko´s signature paintings are iconic, like Warhol´s soup cans, Dali´s Camembert watches, Raphael´s little angels in the Sistine Madonna, Michelangelo´s Creation of Adam, Leonardo´s Mona Lisa, or Duchamp´s urinal. If you have managed to come up with something iconic, then you have most likely triumphed over other frailties that there might be. In his comparative superficiality, Rothko is perhaps more profound, deeper, universal than Newman. (Superficial as I am, I still prefer Newman over Rothko.)

Clyfford Still and Radical Otherness

Clyfford Still makes the rest of us look academic.

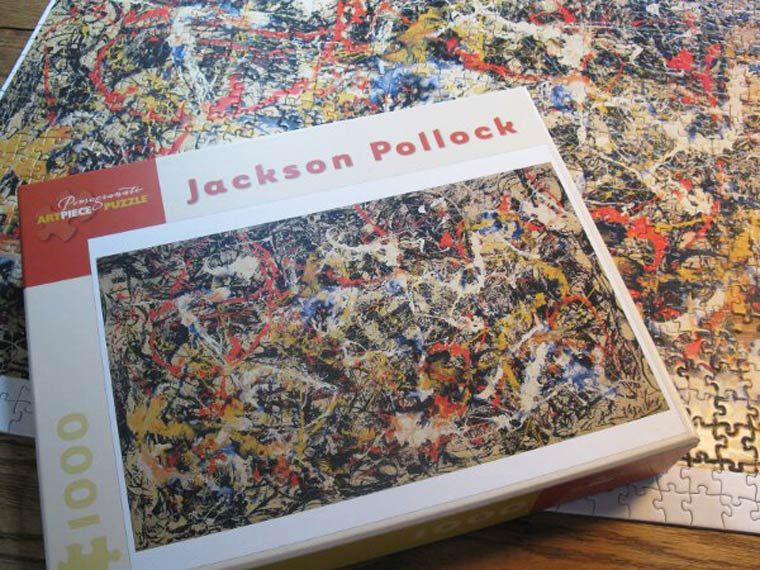

Jackson Pollock

I reiterate: If you want to see the world aright, you need to get in mimetic touch with that that is different from you, you need to embrace the other. By permanently and consecutively embracing the different, the other, your vision will become more and more complete, your vision will become more and more one. There will be no more internal stratification inside you, just an open field (with, to be true, largely heterogenous elements, yet their boundaries will become fuzzy and blurred, i.e. open for interaction). E pluribus unum, or so they say. Clyfford Still was very different, very otherwise. Clyfford Still stands in the corner of another room, enigmatically. It is not easy to decipher what such a figure actually wants to say, it does not directly communicate; it is vibrating and humming in itself, obviously it is alive, but most obviously it is something different from us and from anything we commonly know. Clyfford Still is very original and very different, very unlike anything we know. Maybe it is us who are different – and forsaken – , and he is the one more close to the Real Thing, to the real Real. Or so we might think. Jackson Pollock said, Clyfford Still made the rest of the American painters look academic. He was a forerunner of Abstract Expressionism, developed his “style” in reclusiveness, and he disliked Abstract Expressionism once it had become fashionable, and, as he saw it, sterile and formulaic. So he withdrew from the scene. Ideally, Still´s largely monochromous paintings contain flame-like, wedge-like or eye-like elements that shake up the silence of the undifferentiated primal ground, but add another silence into it, or a language that mumbles, partly comprehensibly, partly unintelligibly. They are the (relative) silence of Otherness, the enigma of Otherness. While the other Abstract Expressionists come up with something vivid, or Barnett Newman comes up with a flashing Zip, out of Clyfford Still´s primal ground emerges some primal, originary Otherness. Silent, though not mute, reclusive. An all-over eye, that seems to envision the entire scene and its beyond. It is face-like, like the paintings of another one who was a radical Other: Wols. The paintings by Wols and by Clyfford Still are like faces of Otherness. We gaze into them, they gaze into us. In some way we do meet, in some other way we don´t. Very different, very otherwise, all that. What is striking is the in-your-face character of these painted faces, of the paintings both by Wols and by Still. They come unfiltered and unmitigated. The poststructuralists (Derrida) say that presence does not exist, but the paintings by Clyfford Still and by Wols are of an unmistakable presence. They seem to be presence itself. They shake up poststructuralism. They confront any systems of meaning with some strange, evasive super-meaning; or with an ultra-meaning and an infra-meaning. They are an extension to ordinary meaning. Clyfford Still probably was the best abstract painter who ever existed (or, upon reflection, Mondrian might have been). Yet, maybe therefore, he is not, or cannot be, a household name like Pollock, Rothko or de Kooning. There seems to be an additional level of abstraction to his paintings; in his paintings there seems to be a meta-level of abstraction and Abstract Expressionism. This is what the ordinary eye cannot truly bear: the eye of radical Otherness, the faces of radical Otherness. The art of Clyfford Still exemplifies radical Otherness.

Concerning Lacan´s “Great Other”, I do not know how individuals like Clyfford Still could be intimidated by the uncanny complexity and intransparency of any “Great Other”. Rather, it will be them who intimidate any other Great Other. If we take the “Great Other” to be language, customs, artistic styles – in the final instance: God – i.e. stuff that preforms and predetermines the individual and its modes of thought and expression, then individuals like Clyfford Still function in some way as the register of the Real to the Symbolic register that holds the Great Other. I.e. they are what evades the register of the Symbolic and predetermined language and modes of expression. They are something else. They are the Great Other to the Great Other. They are originary, and they seem to be primary to the register of the Symbolic (or, they seem to be an uncanny return of the Symbolic that has digested itself and now confronts the Symbolic that is still in place with the radical alterity that lies (not only) within the Symbolic (but in all the registers) – so, in some way they are near to the closure of the entire system of the registers). Lacan says the Great Other is barred. Although we may be inclined to think so, the Great Other is not complete and not identical to itself, just as we aren´t. The Great Other is barred. This kind of non-identity you seem to have in the art of Clyfford Still as well. But this non-identity seems to be much more natural and identical to itself, not as helpless as the non-identity in the Great Other, or inside us, whose non-identity evolves out of our inability to come to terms with ourselves. This is so because otherness is the inherent nature of it, and of such individuals who serve as the Great Other to the Great Other. Their otherness and alterity is primary. They are their own Great Other. They embody their own alterity, they are the embodiment of alterity. They are in natural touch with the other – and therefore with the entire universe. The common categories are: the self and the non-self (the other). But inside them, the self and the other are not separated. (You gotta keep em separated, sing The Offspring. But such individuals, who serve as Great Others to the Great Others, they do not.) Frank Stella says that Clyfford Still´s art seems to come effortless, originating from another place. In this effortlessness, it is unlike any other painting, and Clyfford Still is unlike any other painter. Clyfford Still himself says, in his paintings there should be expressed the amalgamation between life and death. What could be more different, more otherwise to each other than life and death? In the paintings of Clyfford Still you gaze into radical alterity, into radical Otherness.

Jackson Pollock and the Wormhole of Creativity

I reiterate: the goal of the creative process is to enable a transformation. The supreme creator attracts matter of all kind, internalises it, makes it his interior; via heavy intellectual concentration, via introspection, under its own weight and gravity it collapses into a black hole; this will open up a hyperdimensional channel through ordinary spacetime fabric, a wormhole; which will then eject the transformed, channeled, dimensionally challenged, warped interior in a complete other region in space and time, via a white hole. This is, then, a true transformation. Though we have recently managed to detect black holes, no one has ever seen the astronomical object of a white hole. But in creative processes, in the arts, you can, from time to time, encounter white holes. The signature paintings of Jackson Pollock, the drip paintings, are probably most exemplary of such white holes.

Pollock, a ruminative, cautious, uncommunicative fellow, seeked to gain access to the spiritual, the “unconscious”, via ancient symbols, totems, and the like. He was less interested in “figuration” or “abstraction” per se but wanted to express his interior via painting. He also wanted to paint “American”, for which there had been no actual template at that time. Well before he had come up with his drip paintings he already had been the only American artist who was able to free himself from the hitherto predominant European influence and to paint in a truly independent manner. He was the only American painter at this time who was able to achieve this. Like Picasso, Pollock was a great painter in the classical sense. Laypersons may suspect Pollock´s or Picasso´s paintings as “something a child could do”. But it can not. Both Pollock and Picasso were great painters that were in need to push boundaries. Via their breakthrough inventions, they seemingly eliminated boundaries and created a new spacetime, a new dimensionality, where stuff unfolds in all kinds of manners, according to the logic of these dimensionalities. That´s when they became greater than just “great”.

Pollock was explosive and highly energetic all along, but he was also highly introspective and creatively introverted. He was sucked into the abyss of his own creative introspection. When he finally channeled through the wormhole and released his energy through the white hole of his drip paintings, he actually managed to “fully express himself” and “turn his inside out”, to fully deliver, via his action painting, his “unconscious”. There is no distance anymore between himself and his paintings, between his expressions and that what is expressed. That was something new again. From a black hole nothing gets out and into a white hole nothing gets in. A white hole is a permanent explosion. Pollock´s drip paintings are said to be both ecstatic and monumental. They are both dynamic and frozen in a statuariness; they are, creatively, tranquil and calm. The are complete. They are, maybe, the world process from a God´s perspective. From a more mundane standpoint – which is yet extremely elevated and something in its own right as well – Pollock managed to do paintings that cannot be counterfeited or duplicated. What a wormhole! What a white hole!

Black holes, white holes and wormholes are logical, though dimensionally different from spacetime as we know it, or they are spacetime in reverse. Their core, their most interior, remains mysterious nevertheless. Scientists suspect that around a singularity anything can happen, as the common laws of the physical universe break down at this point. In the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock, anything happens.

Pollock, they noted, had a unique perception. He could see moving things and movements per se. He could see things from all angles. He had a superdimensional perception. Art, they demand, should let you gaze into another dimension. In the case of Pollock you see the entire dimensionality of the creative process. That is to say: let your stuff, via introspection, collapse into a black hole, dimensionally channel it though a wormhole, and release it through a white hole, unexpectedly, in some completely other part of the universe. This makes, then, a true transformation.