Deleuze (respectively the Deleuze/Guattari hermaphrodite) says art is about Becoming. Deleuze (respectively Deleuze/Guattari) is very fond of transformations that stem out from the obscure and unexpected (from „chaos“) and lead to new ways of how perceive things. He likes that so much that in his philosophy true „events“ (not subjects, objects, structures, etc.) embody the highest degree of reality since they´re the ones that inflict change on reality. The true artist permanently „becomes“ and calls for „a new earth, a new people“, that is to say for new modes of understanding and being alongside his specific vision which is, if it is of the highest caliber, self-transcendent. Becoming happens at „zones of indistinguishability“ between qualities (for instance that the maltreated, oppressed human becomes animal, the maltreated, oppressed animal becomes human), via his empathy and associative intelligence and powered by his drive to transform and finally to incorporate being in its totality, the true artist is sensitive for spotting and experiencing zones of indistinguishability. Deleuze/Guattari says (with reference to Lawrence) the artist carves slits and openings into the firmament, respectively into common understanding, to let some chaos in, which then allows syntheses of new and higher order. Deleuze/Guattari also says that the artist, in a way of defying chaos, tries to reach into the infinite and then tries to project it into the finite i.e. the true artwork being a zone of highest order in which the infinite shines trough. Deleuze says, if we try to understand art and artists in such ways, i.e. as people that dive into the unknown solely for the sake of achieving knowledge and transformation of mind, artists who write „minor“ literature, only, actually, a small minority of people doing art could be labelled artists (respectively writers, as he is, in the respective text – Literature and Life – specific about literature).

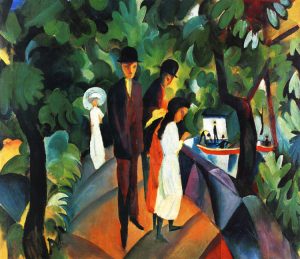

Ranciére understands aesthetics, as well as politics, as regimes which legitimise certain objects/subjects/entities as theirs. The paria, the proletarian, the slave is originally excluded from the sphere of politics; with finding a voice they become political subjects; they are able to participate at the political process, they are included in the political process. Politics does happen when excluded parias become included and transform from (quasi)objects to authentic subjects of politics. Therefore, politics is about finding strategies for the excluded to become included. Likewise, the regime of aesthetics defines what is to considered as beautiful or as art. These regimes are open and in flux. Rancière is concerned about how art could contribute to political change. He makes reference to Schiller and to the idea that art is kind of democratic since the sensual, the aesthetic, can be experienced by everyone, as well as to the idea that art orginates from a ludic drive (Spieltrieb) in man. The playfulness alongside the ludic drive can be seen as opposed to the seriousness of material conditions, as well as where true freedom and the possibility of self actualisation lies, which becomes projected into the vision of a somehow brotherly society of competent, empathetic individuals. Rancière, who has a keener eye on investigating paradoxes (of art, politics, literature, etc.) than offering a stringent philosophy (like Deleuze) says that, in practical terms, political revolutions via aesthetic revolutions largely have failed, degenerating, in the 20th century, into consumer aesthetics in capitalism or Stalinist pomp under communism. (I, however, am quite content with living in a consumer society. Likewise, under specific circumstances there is nothing wrong with being sympathetic with communism. Bolz reminds us that living in a consumer society prevents us from relapsing into religious or ideological fanaticism and extremism, or communism.) Rancière claims that while Deleuze wants to extend philosophy into spheres that are external to philosophy, he himself is rather interested in using philosophical understanding and method in other playgrounds of the human mind, or in the most practical arenas. He is also skeptical of Deleuze´s notion of philosophical concepts or books as „tools“/“toolkits“, given the emptiness of many texts in which others try to use the Deleuzian tools, and he confirms that Deleuze establishes a kind metaphysical imaginary that is alien to him. He seems to have a need for precision that may rather be found in the writings and approaches of Deleuze´s temporary friend, Foucault. — Rancière´s text „Is Art Resistant?“ provided the ferment of this text, and I am glad that after weeks of intellectually working on it i now finally seem to be able to get the fucking thing done.

So there you have the art genius, trying to look at the world in order to determine its value – the artist, spiritualised with empathy and sense for connection and therefore trying to spiritualise the objects of art, trying to establish connection and communion in the world — with his vast intellect he sees abstractions and general modes of being in the individual and the idiosyncratic as well as he sees the individualities and idiosyncracies which evade the abstractions. He sees occasional gestures and movements full of grace, in a specific way a person laughs for instance, which give him awareness of the presumably graceful nature of the world and of people — a giant, a cosmic spectacle before his eyes, in his mind ———– which unfortunately effectively gets contrasted via a more sober look on the world: In which most people, effectively, are not specifically intelligent nor equipped with pleasant personalities. Their epistemology is simple and they can´t think, which is why offering genuine innovative philosophy and art is about the same as trying to offer a paper on advanced topology or differential geometry to people – it is equally incomprehensible to them although it is (apparently) written in the same language they use, not in the language of mathematics. Likewise, beauty is, indeed, recognisable for everyone, just most people don´t care a lot about it, let alone that they were able to understand beauty on a more abstract level and intellectualise it in order to solidify their understanding and enliven it (with those intelligent enough to intellectualise stuff often not being receptive to beauty or genuine creativity in turn), same goes for originality. Despite people are quite self-centered they usually don´t even know how to dress themselves properly. Look at how people are running through the city or sitting in restaurants and obviously take a look at nothing – whereas my own sight usually roams and roves and tries to look at my surroundings their glimpses don´t! They are, to a considerable degree, not interested in the world they inhabitate, let alone in that which is beautiful, intelligent, vibrant, etc. but in stuff and people in which they can mirror themselves, which is why slightly above average people often are so popular (since average people can project themselves into them) whilst it is often a hindrance to success being very much above average. People like to complain a lot and they´re negativistic, they demand that „more intelligence“ should happen or „true art“ should happen, but when it does happen they regularly don´t pay attention. When they see that intelligence comes around the corner but does not confirm their pre-existing world views, they may hate it. The problem of intelligent artists is that they want to make people more intelligent, but, in the first place, they make them look stupid as they confront people with something they cannot properly understand; and people don´t like that. That is when their „sapiosexuality“ usually ends. Paradoxically, the great genius who establishes the most potent worldview by thinking outside all contemporarian boxes is what is least desired or acknowledged. There may be nothing (of substance) the world is less interested in, and less friendly to, than a truly original thinker as long as he isn´t recognised and verified by the machine. (Meditate about that.) So much for the polemic.

Likewise, beauty is, indeed, recognisable for everyone, just most people don´t care a lot about it, let alone that they were able to understand beauty on a more abstract level and intellectualise it in order to solidify their understanding and enliven it (with those intelligent enough to intellectualise stuff often not being receptive to beauty or genuine creativity in turn), same goes for originality. Despite people are quite self-centered they usually don´t even know how to dress themselves properly. Look at how people are running through the city or sitting in restaurants and obviously take a look at nothing – whereas my own sight usually roams and roves and tries to look at my surroundings their glimpses don´t! They are, to a considerable degree, not interested in the world they inhabitate, let alone in that which is beautiful, intelligent, vibrant, etc. but in stuff and people in which they can mirror themselves, which is why slightly above average people often are so popular (since average people can project themselves into them) whilst it is often a hindrance to success being very much above average. People like to complain a lot and they´re negativistic, they demand that „more intelligence“ should happen or „true art“ should happen, but when it does happen they regularly don´t pay attention. When they see that intelligence comes around the corner but does not confirm their pre-existing world views, they may hate it. The problem of intelligent artists is that they want to make people more intelligent, but, in the first place, they make them look stupid as they confront people with something they cannot properly understand; and people don´t like that. That is when their „sapiosexuality“ usually ends. Paradoxically, the great genius who establishes the most potent worldview by thinking outside all contemporarian boxes is what is least desired or acknowledged. There may be nothing (of substance) the world is less interested in, and less friendly to, than a truly original thinker as long as he isn´t recognised and verified by the machine. (Meditate about that.) So much for the polemic.

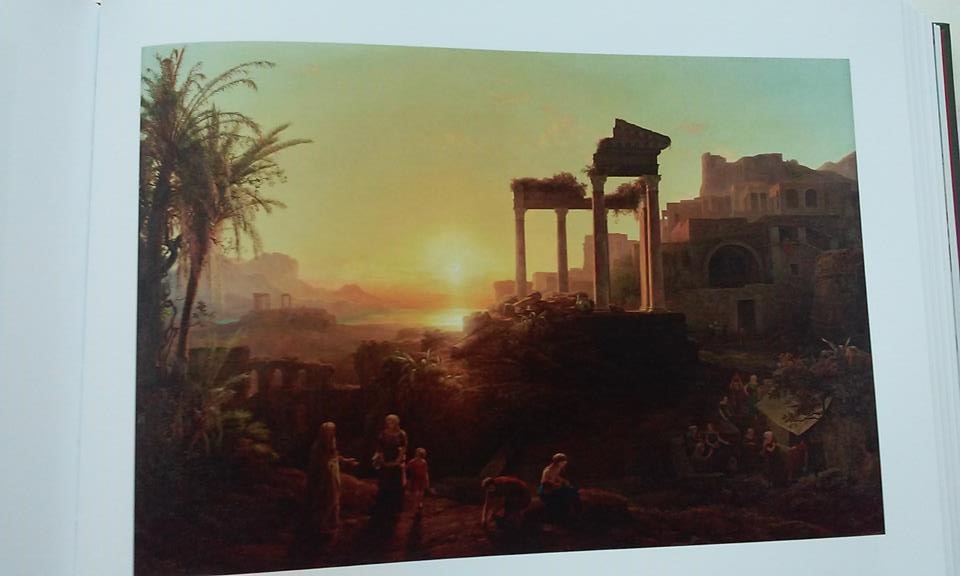

Houellebecq says, while the artist tries to make the world an object of art, the world actually does not at all qualify as an object of art: the world is bluntly rational, without any magic and without particular interest. With that being one of Michel´s usual pessimisms it can actually be, occasionally, quite a nuisance, when the artist and the genius tries to get his firm and powerful, secure grasp on the world and what he grasps into is a kind of foam of stunted or irrelevant understandings, a kind of Emmentaler cheese with a lot of holes and air between the solid structure. This kind of foam is, actually, the world. To many artists it therefore becomes apparent that we are living in a kind of ghost world and then they write sad novels. I find this exaggerated. Foam can be quite beautiful, it changes or vanishes after a while, the foam of the world is stratified and consists of different, and distinguished elements. Art is about giving a lucid impression of the world. Great art is about seeing the universal in that which is transitory, and, therefore, bringing both to life in making it comprehensible for us. Art helps us in understanding a heterogenous and manifold world in which most things forever happen beyond our horizon, not only as it broadens our horizon but as it charges the world, and entitities within the world, with meaning. It illuminates the world as it illustrates the situation of man. Even it is a sad or drab world presented, the intellect rejoices because it makes him see and understand how the pieces fit – „Was im Leben uns verdrießt, man im Bilde gern genießt“ says Goethe. Personal consolation or the possibility to make sense of one´s own situation may also be found in works of art. It gives dignity to the fallen (and may actually be the truest form to deal with horror). And indeed, a work of art may give identity to a people, if not a system of meaning. Identity is good, being equipped with a system of meaning is good, since it increases competence (and gives people a „voice“).

Heterogenousness, due to individuality, is a some kind of oppositional force against reconciliation, and the „new earth“, the „new people“ will be heterogenous all alike. The prospects of a „we all shall come together“, of a reconciled world, are dim since we aren´t all alike. If we were all alike, humanity would cease to exist (and intelligence would cease to be competent since there would be no individuals of above average intelligence to tell the collective what to do). (For instance in the „hellish“ virst volume of Dead Souls) Gogol shows how „individuality“ commonly simply is a nuisance, resulting from lack of heart, mind and soul (not from excess), a mode in which stupidity is displayed. Because of stupidity, reconcilement decreases to become an option. In another dimension, of course, individuality is that which is productively resistant against totalitarian visions of reconcilement, and strong individuality is necessary to evade the influence of other powerful artists. Finally, the extreme individualism of the genius provides the locus of truth since due to his extreme individualism the genius is able to discover authentic human values. The paradox, or the tragedy, is that the genius will forever be alone in his visions and profoundly isolated from society, even if he gets appreciated by society. Whitehead remarks the malady of this world is that average elements can easily be reconciled while the progressively individualistic elements cannot or may even be sorted out or destroyed in the process that makes reality, despite embodying a higher extend of truth. (I, however, advocate the notion that the more individualistic, the more „real“ elements operate at different and distinguished levels of reality and it is probably a good thing that interference between these levels is limited; it need not add up or may be well dangerous to both.) Deleuze says art is about trying to reconcile the „originals“ (genuinely original people) with society (Bartleby or the Formula).

Heterogenousness, due to individuality, is a some kind of oppositional force against reconciliation, and the „new earth“, the „new people“ will be heterogenous all alike. The prospects of a „we all shall come together“, of a reconciled world, are dim since we aren´t all alike. If we were all alike, humanity would cease to exist (and intelligence would cease to be competent since there would be no individuals of above average intelligence to tell the collective what to do). (For instance in the „hellish“ virst volume of Dead Souls) Gogol shows how „individuality“ commonly simply is a nuisance, resulting from lack of heart, mind and soul (not from excess), a mode in which stupidity is displayed. Because of stupidity, reconcilement decreases to become an option. In another dimension, of course, individuality is that which is productively resistant against totalitarian visions of reconcilement, and strong individuality is necessary to evade the influence of other powerful artists. Finally, the extreme individualism of the genius provides the locus of truth since due to his extreme individualism the genius is able to discover authentic human values. The paradox, or the tragedy, is that the genius will forever be alone in his visions and profoundly isolated from society, even if he gets appreciated by society. Whitehead remarks the malady of this world is that average elements can easily be reconciled while the progressively individualistic elements cannot or may even be sorted out or destroyed in the process that makes reality, despite embodying a higher extend of truth. (I, however, advocate the notion that the more individualistic, the more „real“ elements operate at different and distinguished levels of reality and it is probably a good thing that interference between these levels is limited; it need not add up or may be well dangerous to both.) Deleuze says art is about trying to reconcile the „originals“ (genuinely original people) with society (Bartleby or the Formula).

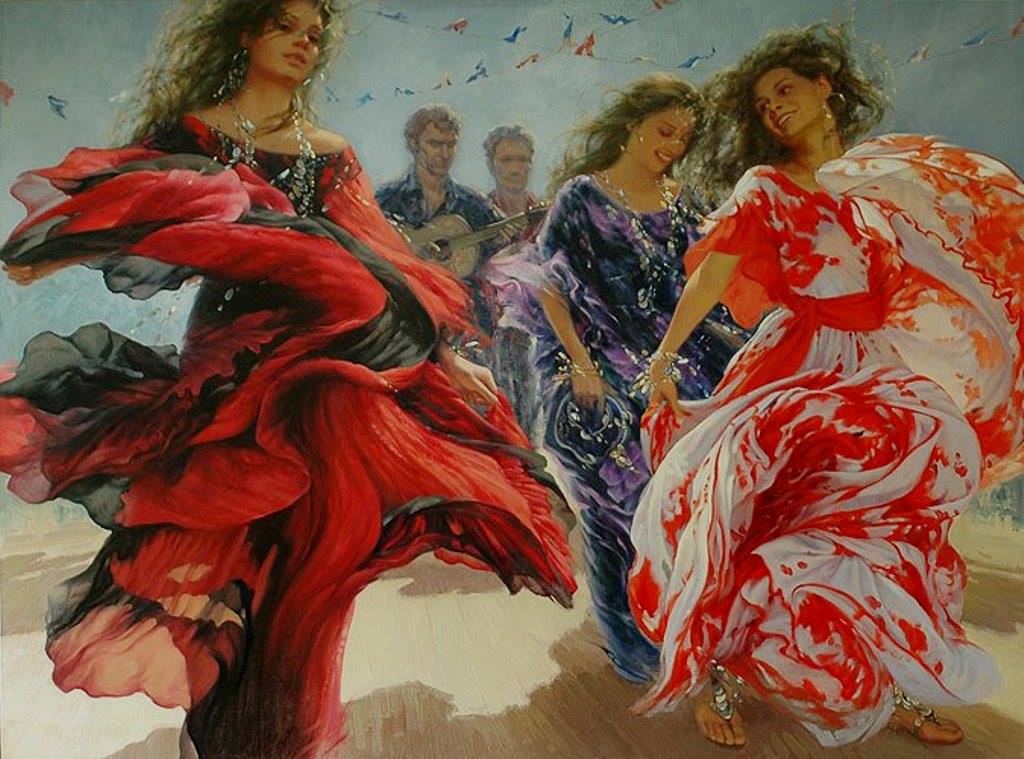

Rancière meditates a good deal about how the specific qualities inherent in art and qualities that make the political may meet, although, with reference to Kant, he emphasises on the sensual and aesthetic qualities and is quite silent about the intellectual qualities of art. – I say maybe the most important quality of the artist is universal empathy. It is his way to relate to the world. Without that his experience of the world can´t be enlivened. Empathy is both an emotional and an intellectual quality and it is noted that exceptionally gifted persons display a high amount of empathy also in their intellectual undertakings (they become unusually immersed in them and de/transpersonalise, etc.). Likewise, art is primarily an expression of associative intelligence which does not primarily aim at exposing the logical structure but the multilayeredness and manifoldness of the world. Divergent thinking is more important than convergent thinking for the artist. As divergent thinking primarily aims at reflecting upon a concept the way of how it could be viewed upon differently, the artist naturally runs (to some degree) against the grain. His intelligence is subversive and his divergent thinking makes him comprehend (and master) chaos. His intelligence expresses itself in an experimental way and opens itself into an evolving future. Associative thinking gives a sense of universal „connectedness“ and a longing for cohesion. Because of that the artist has a strong sense for establishing (authentic) communion between people and between things (which may deem the rest of humanity whimsical or fantastical). While, with reference to Kant, the qualities of the aesthetic (beauty and the sublime) and the qualities of reason and of ethics are distinct, beauty gives us an idea of transcendent order and the sublime fills us with awe for a higher (ethical) instance (deus (absconditus)) to which we have to bow down. Beauty refers to constructiveness and love, the sublime to humility, self-reflection, etc. as a necessary ingredient of how to do things right. Art, therefore, is both contained in itself and self-transcendent. It is both concrete and universal. Art gives a sense for the ambiguity of things and (their embeddedness in) contexts. It opens a dialogue between the empirical and the transcendental. Because of that it is, somehow ironically, the artist, not the scientist, who sheds light on the „thing in itself“. In seeing the universal in the transitory, the multilayeredness and ambiguity of things and contexts, cosmos and chaos, the artist grasps a „meta-noumenal“ essence of a thing, which is „nothing less than the existential ontology of the object, another way of expressing its circumstantial semantic content, now and later on, a mind´s view of ,objective reality`“, as Angell de la Sierra of Omega Society wonderfully makes it explicit of what is apparent to the artistic gnostic in one or the other way and what the art gnostic expresses in one or the other terminology.

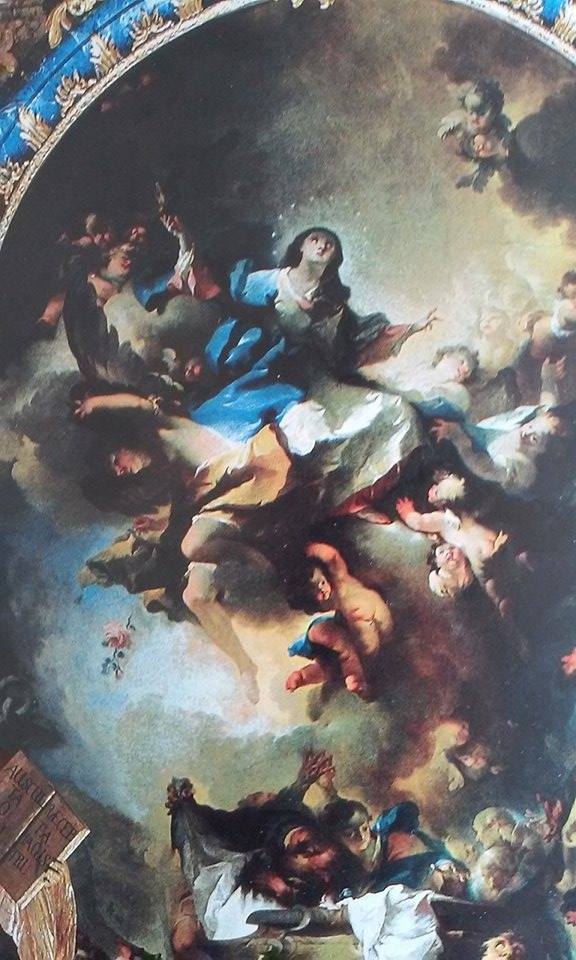

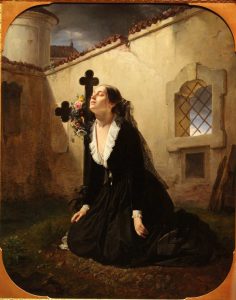

The world may be a terrible disappointment for the artist, and it will be so with growing, painful intensity for the omega artist. Yet of course art requires non-art. Beauty erects upon ugliness, the sublime upon our limitedness, the spheres upon suffering. The isolation of the true artist and thinker may be profound and eternal, but without individual elevatedness upon the collective no intelligence and no transformation and progress can ever be possible. Nietzsche, who embodied extreme intelligence and originality, with the consequence of being also the embodiment of an outcast, sadly philosophised that the world can only be justified as an aesthetic phenomenon. As an aesthetic phenomenon the world, however, necessarily must contain stuntedness; Whitehead somehow proposes that God´s will is not to make the world perfect in the ethical sense but aesthetically and therefore allows stuntedness and decay to enforce creativity and to bring in the new. Consider the world as an artwork by God. This is difficult for the human mind to grasp, but, as stated above, intertwined with that, art may offer consolation. Stuntedness may appear beautiful and fascinating. Since before the inner eye of the artist there is constantly something emerging, evolving, if not protuberating, there is no actual stuntedness. With respect to what is important for Deleuze, the artist´s gaze both sees the actual but also the virtual. The „new earth“, the „new people“ is, therein, a virtual quality. It is also, somehow, „out there“ in this world. For practical and metaphysical reasons we should embrace pluralism and the understanding that the world, when trying to grasp it in totality, becomes elusive, opening itself to an understanding that it consists of many worlds (as Markus Gabriel and New Realism annotate).

The world may be a terrible disappointment for the artist, and it will be so with growing, painful intensity for the omega artist. Yet of course art requires non-art. Beauty erects upon ugliness, the sublime upon our limitedness, the spheres upon suffering. The isolation of the true artist and thinker may be profound and eternal, but without individual elevatedness upon the collective no intelligence and no transformation and progress can ever be possible. Nietzsche, who embodied extreme intelligence and originality, with the consequence of being also the embodiment of an outcast, sadly philosophised that the world can only be justified as an aesthetic phenomenon. As an aesthetic phenomenon the world, however, necessarily must contain stuntedness; Whitehead somehow proposes that God´s will is not to make the world perfect in the ethical sense but aesthetically and therefore allows stuntedness and decay to enforce creativity and to bring in the new. Consider the world as an artwork by God. This is difficult for the human mind to grasp, but, as stated above, intertwined with that, art may offer consolation. Stuntedness may appear beautiful and fascinating. Since before the inner eye of the artist there is constantly something emerging, evolving, if not protuberating, there is no actual stuntedness. With respect to what is important for Deleuze, the artist´s gaze both sees the actual but also the virtual. The „new earth“, the „new people“ is, therein, a virtual quality. It is also, somehow, „out there“ in this world. For practical and metaphysical reasons we should embrace pluralism and the understanding that the world, when trying to grasp it in totality, becomes elusive, opening itself to an understanding that it consists of many worlds (as Markus Gabriel and New Realism annotate).

Deleuze says philosophy is not a power. „Religion, the state, capitalism, science, the law, public opinion and television are powers, but not philosophy.“ Same would apply for art. Since philosophy (art) is not a power it can also not enter into open battle with any power, rather it establishes a guerilla. It is true that the logics of art and of politics are distinguished. Science is the art of grasping the rational aspects of existence, whereas art is the science of investigating the irrational aspects of existence (i.e. the subjective embeddedness of man in nature). They´re different territories. Yet knowledge and understanding vice versa also allows the own and private territory to be understood and explored in greater depth. Who is more powerful is a question of perspective. Finally, it´s only the great works of art which last forver, as the artist may be oppressed, maybe destroyed by any power, but it is him who sees all the kingdoms rise and fall before his inner eye. The powers are transitory, art is the universal. In his downfall, the artist embarrasses and humiliates the powerful transitory victor – who is, then, the vanquisher? Deleuze/Guattari say a true work of art is erected and can stand for itself. Rancière reminds us of the blunt autonomy, the „unavailability“, the statutory character of the statue/artwork, as the autonomy of art and the virtual indifference the l´art pour l´art towards politics carries a moment of resistance, and finally concludes that art is resistant as it does not only enter a dialogue with the political and the transitory but also eternally refuses to do so. Art is its own affirmation, and an affirmation of life. It seeks the liberation of life. It is expression of a liberated, and higher consciousness. It may contain more of the world than the world itself does. And with that I ascend into the regions of the ice mountains and lose myself to never return. Hahahahaha!